The Savages of St. Louis

“The Philippine exhibit is, in fact, an exposition in itself, which cost the Insular Government nearly two millions of dollars, and offers to visitors in a single day a broader knowledge of the Philippines than could be gained by a trip of months duration and the expenditure of many hundreds of dollars.”[1] –New York Times, 1904

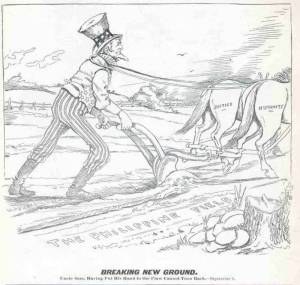

The exposition in St. Louis opened its gates on April 30th, 1904. The fair was a commemoration of the Louisiana Purchase and Lewis and Clark’s expedition. The St. Louis Exposition was, in essence, a true celebration of empire. It marked the centennial anniversary of when America began its policy of westward expansionism. Fair planners were awarded with $15 million to be used for The Lewis and Clark exposition. Ironically, the same exact figure the American government spent on the Louisiana Purchase.[2] The incorporation of recently acquired American colonies represented the beginning of a new stage of Manifest Destiny. The official publication of the exhibition declared “ the time is coming when the purchase and retention of the Philippine Islands will seem as wise to our descendants as does the Louisiana Purchase seem to us who live today.”[3]

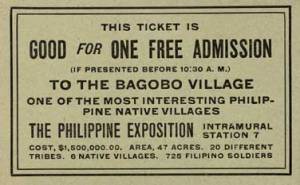

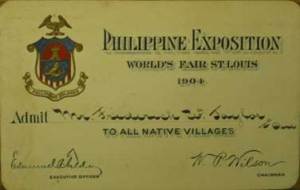

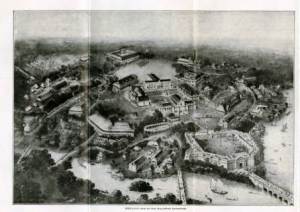

The sheer size of the exhibition was remarkable, spanning over 664 acres making it “the largest international exposition the world had ever seen.” [4] Space reserved for the exhibits was set at 82 acres. The Philippine Reservation dominated the exposition, covering 47 acres, more than half of the total space set aside for exhibits. [5] The racial hierarchy established in Omaha and Buffalo would persist throughout the fair in St. Louis. Members of the Philippine Reservation were often compared to Native and African Americans, by fairgoers and newspapers alike. Unlike these other fairs, a racial hierarchy was established within the Filipino Village. The reservation was home to a number of tribes; the Igorots, the Bagabos, the Visayans, the Negritos, and many more. Each had their own display, in order to illustrate the different steps of civilization. Parezo describes the environment as “villages were arrayed in an evolutionary scheme, beginning with the “lowly” and “wild” Negritos, followed by the more advanced but still “primitive” Igorot, and finally the Visayans, the “highest type” of tribal peoples.”[6] As the American Insular government was experiencing civil unrest abroad, it became imperative not only to convince the American public of the benefits of a positive relationship, but the Filipinos as well.

The organization of the Philippine began in 1903, after Congress passed Act 514, which created the Philippine Exposition board. A New York Times article announced the Filipino Village. The article discusses the scope of the exhibit along with its authenticity. According to the Times the village would “consist of thousands of persons, showing every character in life which exists on the island,” declaring that “the colony will be reproduced as it exists on native soil, and to make it especially realistic homes of the peasantry will be transported from the Philippines.”[7] It was important to the press along with the fair’s planners, that the displays were represented as realistic, while in hindsight they were anything but. Taft and Roosevelt approved of the idea, believing that it would have a pacifying effect on the Filipinos, a trait that they could bring back to the islands.[8] In a letter Taft sent to the Board, he provided instructions for the preparation of the exhibit. The letter also called for the organization of a preliminary exposition to be held in the Philippines, with a permanent museum to be constructed in Manilla.[9] The Board was made up of twenty or so scientist from various fields. The fair in St. Louis was deeply rooted in anthropology. The exposition’s Department of Anthropology was the largest of all previous world fairs.[10]

The department was headed by William John McGee, a prominent scientist and former member of the Bureau of American Ethnology. McGee was also a firm believer in the existence of a racial hierarchy, which he backed with “science.” McGee describes the difference among races as various “advancements of culture and civilization in which “the white man can do more and better than the yellow, the yellow man more and better than the red or black.”[11] McGee believed that “the peoples of the world may be grouped into several races; classes in terms of what they can do rather than what they are…they are grouped into 4 culture grades of savagery, barbarism, civilization, and enlightenment.” [12] He planned to illustrate the various tribes of the Philippines in the same light, each assigned to one of his “cultural grades.” McGee’s belief in Anglo-Saxon supremacy was easily identifiable in his works. In terms of imperialism he felt that “it is the duty of the strong man to subjugate lower nature, to extirpate the bad and cultivate the good among living things”[13] Many of the fair’s planners, as well as white Americans, shared McGee’s view on race. Reflecting on the fair, W.J. McGee published an article titled “Strange Races of Men.” In the article McGee discussed the characteristics of the many ethnicities present at the world fair. He goes on to say “The trace of human progress may be traced in a general way from the ethnic and cultural types assembled on the grounds, under the Department of Anthropology, in the Philippine display.”[14] The various tribes of the Philippines represented the numerous types of civilization. Thousands of artifacts were brought in from the Philippines in order to demonstrate Filipino technology, or lack thereof, as well as the archipelago’s natural resources and their potential. The mission of collecting artifacts rested with Gustavo Niederlein, the Director of Exhibits.[15] The excursion lasted over two years. Upon his arrival in the States, Niederlein returned with over 75,000 artifacts from the islands.[16] Rydell described Niederlein as “a naturalist and scientist devoted to the advance of Western imperialism.”[17] Neiderlein’s work would not go unnoticed. His desire to demonstrate the positive side of imperialism would be received by the fairgoers. The most important part of Neiderlein’s task was to provide a seemingly “authentic” Filipino village. As the fair was underway, the Philippine Exposition Board issued a report on the status of the reservation. The described the exhibit as above all else “an honest one,” declaring “in all respects, commercially, industrially, and socially, the exhibit is a faithful portrayal.”[18] The Philippine exposition was carefully planned to demonstrate the necessity for American imperialism in the Philippines, while simultaneously illustrating how America would provide economic relief for the islands, ultimately furthering the progress of the Philippine people.

On June 18th, as the fair was well underway, the Exposition President Francis held a dedication ceremony for the Philippine Reservation. For the first six weeks of the fair, the Filipino Village had been a raving success, reigning in $3,000 to $5,000 per day. This was quite an impressive figure when accounting for ticket prices: a flat rate of on 25 cents.[19] In his speech, Francis reported that since the fairs opening ninety-nine out of every one-hundred fairgoers had visited the Philippine exhibit.[20] The Filipino Village’s size was only surpassed by its extravagancy. The exhibit was a commemoration of America’s victory in the Spanish-American War. Upon entry, fairgoers crossed the “Bridge of Spain” which would bring them into the “Walled City.” The Walled City was a replica of Manila’s fort, which to no surprise, was headed by the War Department “where fairgoers could relive the recent military triumphs by the United States.”[21] Within the fort, visitors could view photographs the depicted America’s most recent military conflict. The fort was also home to an array of American weaponry, spanning over the last century. As the fairgoers left the fort, they travelled over bridges constructed from bamboo: signifying a transition from the American influence found in the War Department’s to the life of the uncivilized Filipino. After crossing the bridge, visitors could choose from 3 different themed areas: the current state of the islands, the Spanish Occupation, and the American Influence. [22]

The villages of the Philippine Reservation presented a vast array of Filipinos. The most popular of the tribes being the “dog-eating” Igorots, the “tree dwelling “Negritos, and “culturally advanced” Visayans. The Igorots and Negritos were placed in adjacent villages. Their encampment was encased by the Philippine Scouts and Constabulary, the paramilitary force tasked with assisting the United States’ efforts to put down the rebellion in the Philippines.[23] The Constabulary and Scouts presence at the fair was meant to authenticate the ideas of authority through military might to the masses.[24] The Constabulary was strategically placed within close proximity to the Igorots and Negritos to illustrate the “extremes of the social order in the islands.”[25] Member of the Scouts and the Constabulary played a significant role by illustrating what steps the American government had taken in terms of civilizing the savage. The Philippine Constabulary Band, or PCB, gave many concerts throughout the course of the fair, always finishing the show with a lively rendition of the Star-Spangled Banner to depict American influence.[26]

The Philippine Constabulary were perceived as civilized people. Shortly after their initial appearance, schoolteachers from St. Louis began requesting the men join them on tours of the exposition. White men grew furious over the site of a Filipino handing hands with a young white girl. Talusan assesses the situation: “Fear of non-white male sexually preying on white women, anxiety over racial contamination, and insecurity about their social dominance easily inflamed white males.”[27] As tension grew to dangerously high levels, groups of white men soon turned violent. When seen in the courtship of a white woman, Caucasian males taunted the Filipinos with derogatory terms, calling out “nigger” as they walked by. When that didn’t work, white men turned to physical violence, tackling the member of the Constabulary to the ground, which was followed by any number of kicks to the midsection and head. The tension finally reached a boiling point in late July, culminating in a deadly brawl pitting the Constabulary against marines.[28] According to Rydell, the marines were “determined to show the Filipinos that lynch law was not limited to southern blacks. [29] During the tussle a white man was stabbed, tarnishing the reputation of the Constabulary. To the fairs planners and imperialists, this showed that their efforts had not gone unnoticed. In fact, the result of the conflict illustrated that the fair’s misrepresentation had worked, as Americans viewed them as a lower, uncivilized people.

[1] “Typical Life on the Islands Revealed” New York Times. July 17,1904

[2] Rydell, All the World’s a Fair, p 157

[3] Rydell, All the World’s a Fair, p. 167

[4] Rydell, All the World’s a Fair, p. 157

[5] “Filipinos at the World Fair” New York Times, May 25, 1903.

[6] Parezo “The Exposition within the Exposition” Gateway Heritage 112, no 4.2004, p28

[7] “Filipinos at the World Fair,” New York Times, May 25, 1903

[8] Rydell, All the World’s a Fair, p. 168

[9] William Taft “Circular Letter of Governor Taft” 1903, Library of Congress

[10] Rydell, All the World’s a Fair p. 160

[11] Rydell, All the World’s a Fair p. 160

[12] Rydell, All the World’s a Fair p. 161

[13] Rydell, All the World’s a Fair p. 161

[14] W.J. McGee “Strange Races of Men” Doubleday, Page and Company, August 1904

[15] “Report of the Philippine Exposition Board” Greeley Printing, St Louis, 1904

[16] Parezo “The Exposition within the Exposition,” 2004. pg 31

[17] Rydell, All the World’s a Fair, 168

[18] “Report of the Philippine Exposition Board,” 1904.

[19] Parezo “The Exposition within the Exposition,” 2004. P. 31

[20] Parezo “The Exposition within the Exposition,” p. 31

[21] Rydell, All the World’s a Fair, p. 170

[22] Parezo “The Exposition within the Exposition,” p. 32

[23] Mary Talusan, “Music, Race, and Imperialism” Philippine Studies, 2004, p. 499.

[24] Mary Talusan, “Music, Race, and Imperialism” p.504.

[25] Rydell, All the World’s a Fair, p 171

[26] Mary Talusan, “Music, Race, and Imperialism” p.506

[27] Mary Talusan, “Music, Race, and Imperialism” p.518.

[28] Mary Talusan, “Music, Race, and Imperialism” p.518.

[29] Rydell, All the World’s a Fair p. 177